Anatomy

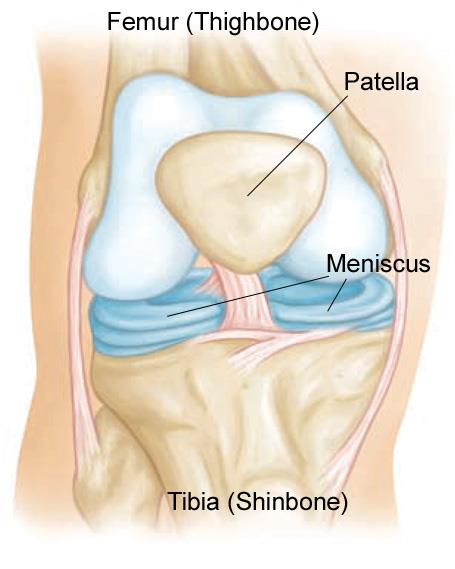

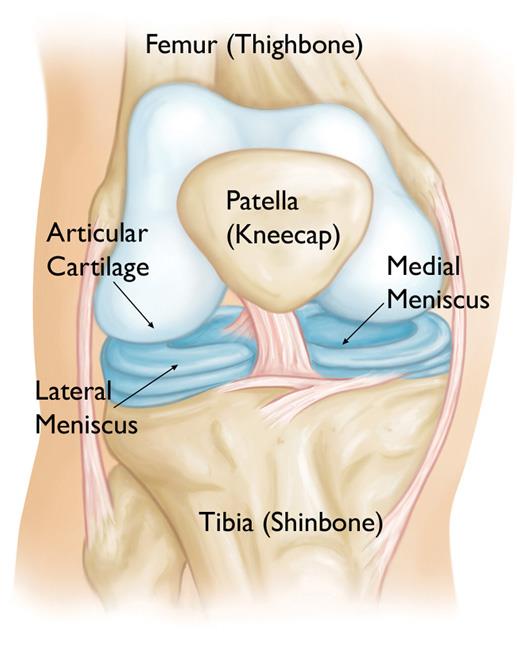

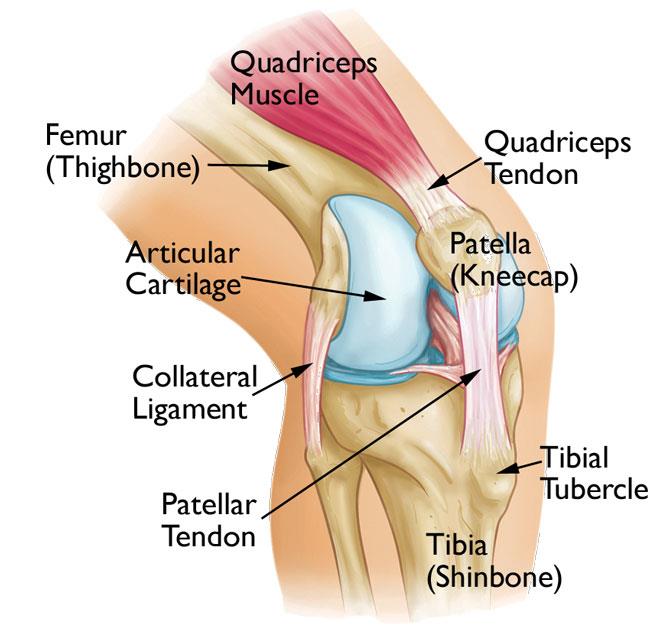

Three bones meet to form your knee joint: your thighbone (femur), shinbone (tibia), and kneecap (patella). Your kneecap sits in front of the joint to provide some protection.

Bones are connected to other bones by ligaments. There are four primary ligaments in your knee. They act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

Collateral Ligaments

These are found on the sides of your knee. The medial collateral ligament is on the inside and the lateral collateral ligament is on the outside. They control the sideways motion of your knee and brace it against unusual movement.

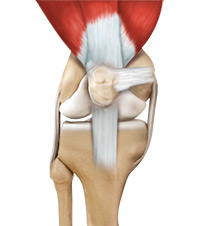

Cruciate Ligaments

These are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an “X” with the anterior cruciate ligament in front and the posterior cruciate ligament in back. The cruciate ligaments control the back and forth motion of your knee.

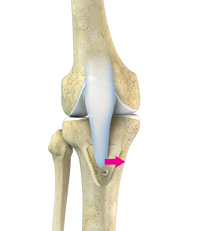

The anterior cruciate ligament runs diagonally in the middle of the knee. It prevents the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur, as well as provides rotational stability to the knee.

Description

About half of all injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament occur along with damage to other structures in the knee, such as articular cartilage, meniscus, or other ligaments.

Injured ligaments are considered “sprains” and are graded on a severity scale.

Grade 1 Sprains. The ligament is mildly damaged in a Grade 1 Sprain. It has been slightly stretched, but is still able to help keep the knee joint stable.

Grade 2 Sprains. A Grade 2 Sprain stretches the ligament to the point where it becomes loose. This is often referred to as a partial tear of the ligament.

Grade 3 Sprains. This type of sprain is most commonly referred to as a complete tear of the ligament. The ligament has been split into two pieces, and the knee joint is unstable.

Partial tears of the anterior cruciate ligament are rare; most ACL injuries are complete or near complete tears.

Cause

The anterior cruciate ligament can be injured in several ways:

- Changing direction rapidly

- Stopping suddenly

- Slowing down while running

- Landing from a jump incorrectly

- Direct contact or collision, such as a football tackle

Several studies have shown that female athletes have a higher incidence of ACL injury than male athletes in certain sports. It has been proposed that this is due to differences in physical conditioning, muscular strength, and neuromuscular control. Other suggested causes include differences in pelvis and lower extremity (leg) alignment, increased looseness in ligaments, and the effects of estrogen on ligament properties.

Symptoms

When you injure your anterior cruciate ligament, you might hear a “popping” noise and you may feel your knee give out from under you. Other typical symptoms include:

- Pain with swelling. Within 24 hours, your knee will swell. If ignored, the swelling and pain may resolve on its own. However, if you attempt to return to sports, your knee will probably be unstable and you risk causing further damage to the cushioning cartilage (meniscus) of your knee.

- Loss of full range of motion

- Tenderness along the joint line

- Discomfort while walking

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination and Patient History

During your first visit, your doctor will talk to you about your symptoms and medical history.

During the physical examination, your doctor will check all the structures of your injured knee, and compare them to your non-injured knee. Most ligament injuries can be diagnosed with a thorough physical examination of the knee.

Imaging Tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. Although they will not show any injury to your anterior cruciate ligament, x-rays can show whether the injury is associated with a broken bone.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This study creates better images of soft tissues like the anterior cruciate ligament. However, an MRI is usually not required to make the diagnosis of a torn ACL.

Treatment

Treatment for an ACL tear will vary depending upon the patient’s individual needs. For example, the young athlete involved in agility sports will most likely require surgery to safely return to sports. The less active, usually older, individual may be able to return to a quieter lifestyle without surgery.

Nonsurgical Treatment

A torn ACL will not heal without surgery. But nonsurgical treatment may be effective for patients who are elderly or have a very low activity level. If the overall stability of the knee is intact, your doctor may recommend simple, nonsurgical options.

Bracing. Your doctor may recommend a brace to protect your knee from instability. To further protect your knee, you may be given crutches to keep you from putting weight on your leg.

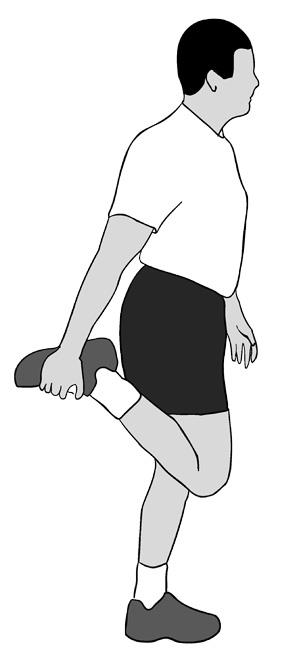

Physical therapy. As the swelling goes down, a careful rehabilitation program is started. Specific exercises will restore function to your knee and strengthen the leg muscles that support it. Surgical Treatment

Rebuilding the ligament. Most ACL tears cannot be sutured (stitched) back together. To surgically repair the ACL and restore knee stability, the ligament must be reconstructed. Your doctor will replace your torn ligament with a tissue graft. This graft acts as a scaffolding for a new ligament to grow on.

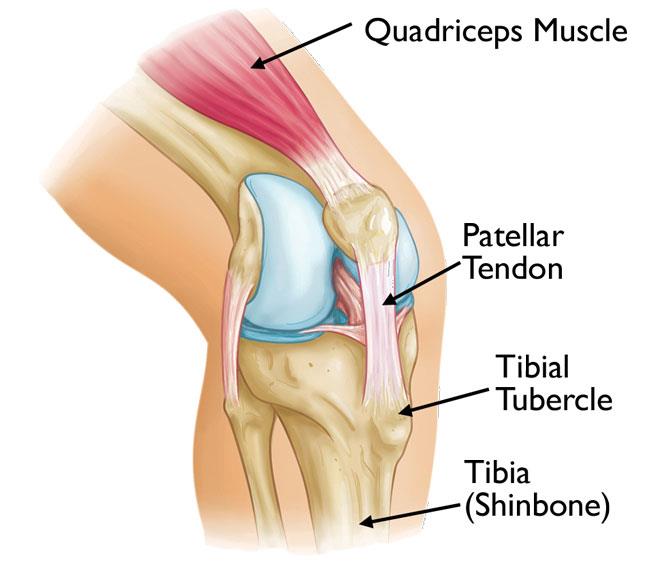

Grafts can be obtained from several sources. Often they are taken from the patellar tendon, which runs between the kneecap and the shinbone. Hamstring tendons at the back of the thigh are a common source of grafts. Sometimes a quadriceps tendon, which runs from the kneecap into the thigh, is used. Finally, cadaver graft (allograft) can be used.

There are advantages and disadvantages to all graft sources. You should discuss graft choices with your own orthopaedic surgeon to help determine which is best for you.

Because the regrowth takes time, it may be six months or more before an athlete can return to sports after surgery.

Procedure. Surgery to rebuild an anterior cruciate ligament is done with an arthroscope using small incisions. Arthroscopic surgery is less invasive. The benefits of less invasive techniques include less pain from surgery, less time spent in the hospital, and quicker recovery times.

Rehabilitation

Whether your treatment involves surgery or not, rehabilitation plays a vital role in getting you back to your daily activities. A physical therapy program will help you regain knee strength and motion.

If you have surgery, physical therapy first focuses on returning motion to the joint and surrounding muscles. This is followed by a strengthening program designed to protect the new ligament. This strengthening gradually increases the stress across the ligament. The final phase of rehabilitation is aimed at a functional return tailored for the athlete’s sport.

Download Pdf

Download Pdf