A rotator cuff tear is a common cause of pain and disability among adults. Each year, almost 2 million people in the United States visit their doctors because of a rotator cuff problem.

A torn rotator cuff will weaken your shoulder. This means that many daily activities, like combing your hair or getting dressed, may become painful and difficult to do.

Anatomy

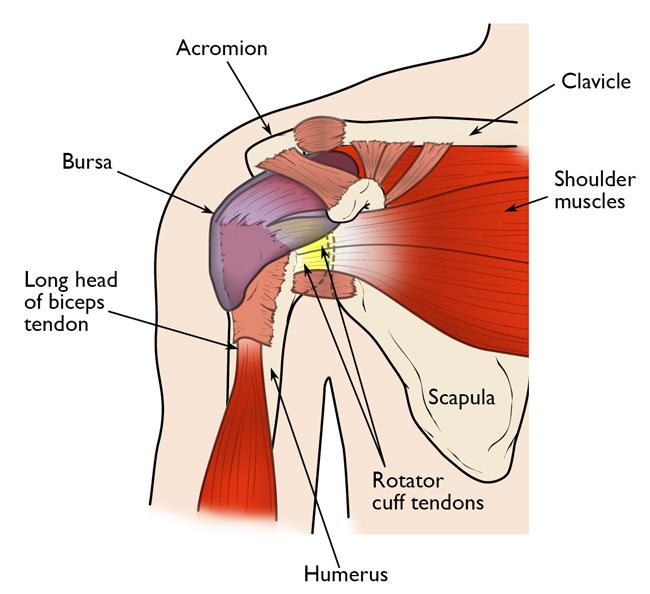

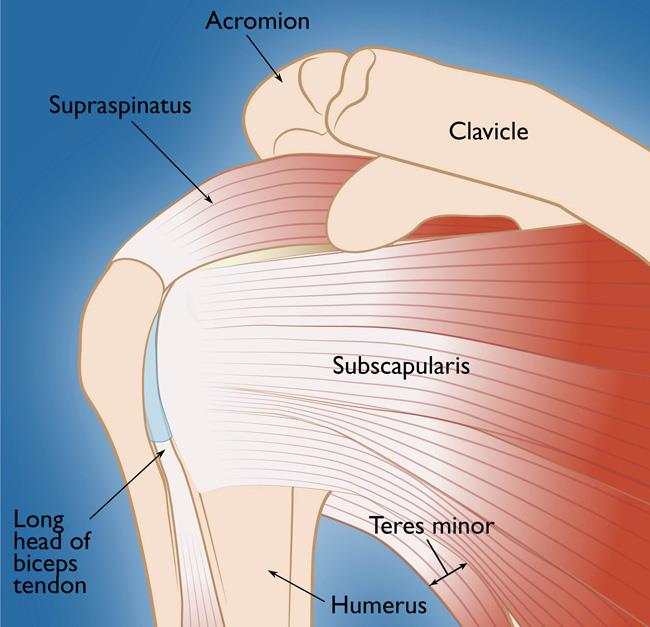

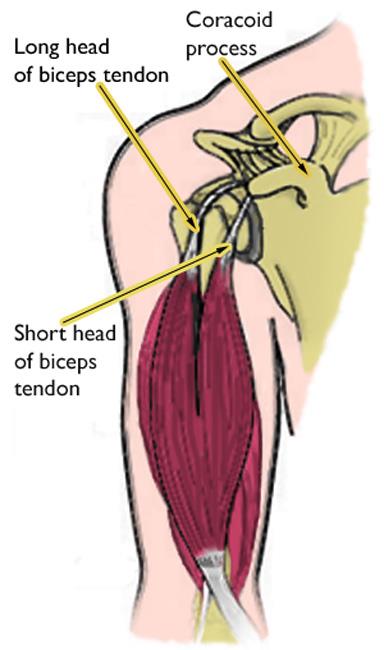

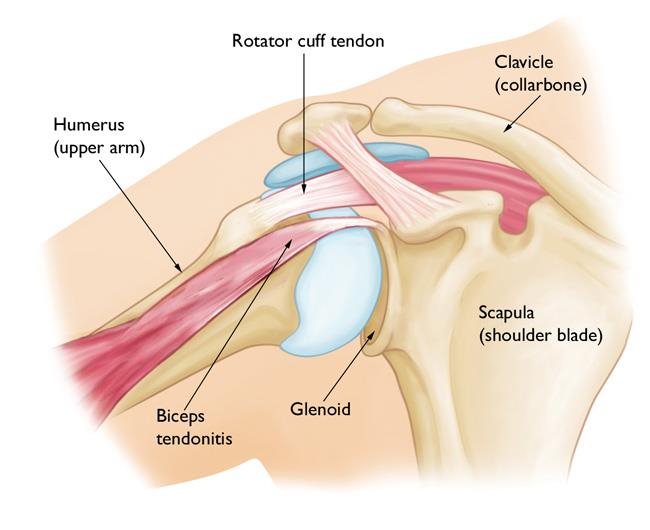

Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle). The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint: the ball, or head, of your upper arm bone fits into a shallow socket in your shoulder blade.

Your arm is kept in your shoulder socket by your rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that come together as tendons to form a covering around the head of the humerus. The rotator cuff attaches the humerus to the shoulder blade and helps to lift and rotate your arm.

There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm. When the rotator cuff tendons are injured or damaged, this bursa can also become inflamed and painful.

Description

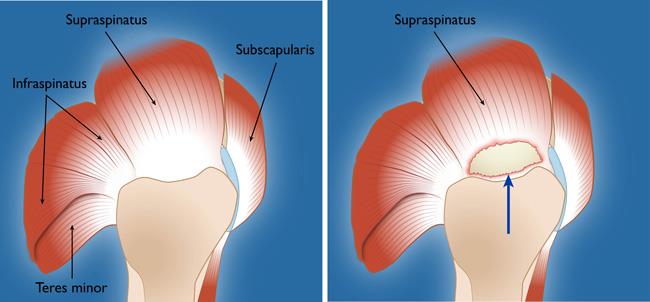

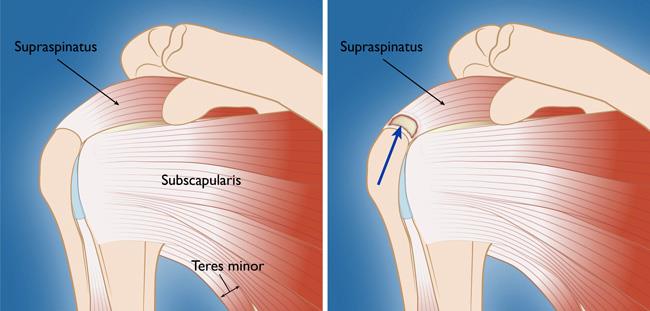

When one or more of the rotator cuff tendons is torn, the tendon no longer fully attaches to the head of the humerus.

Most tears occur in the supraspinatus tendon, but other parts of the rotator cuff may also be involved.

In many cases, torn tendons begin by fraying. As the damage progresses, the tendon can completely tear, sometimes with lifting a heavy object.

There are different types of tears.

- Partial tear. This type of tear is also called an incomplete tear. It damages the tendon, but does not completely sever it.

- Full-thickness tear. This type of tear is also called a complete tear. It separates all of the tendon from the bone. With a full-thickness tear, there is basically a hole in the tendon.

Cause

There are two main causes of rotator cuff tears: injury and degeneration.

Acute Tear

If you fall down on your outstretched arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking motion, you can tear your rotator cuff. This type of tear can occur with other shoulder injuries, such as a broken collarbone or dislocated shoulder.

Degenerative Tear

Most tears are the result of a wearing down of the tendon that occurs slowly over time. This degeneration naturally occurs as we age. Rotator cuff tears are more common in the dominant arm. If you have a degenerative tear in one shoulder, there is a greater likelihood of a rotator cuff tear in the opposite shoulder — even if you have no pain in that shoulder.

Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears.

- Repetitive stress. Repeating the same shoulder motions again and again can stress your rotator cuff muscles and tendons. Baseball, tennis, rowing, and weightlifting are examples of sports activities that can put you at risk for overuse tears. Many jobs and routine chores can cause overuse tears, as well.

- Lack of blood supply. As we get older, the blood supply in our rotator cuff tendons lessens. Without a good blood supply, the body’s natural ability to repair tendon damage is impaired. This can ultimately lead to a tendon tear.

- Bone spurs. As we age, bone spurs (bone overgrowth) often develop on the underside of the acromion bone. When we lift our arms, the spurs rub on the rotator cuff tendon. This condition is called shoulder impingement, and over time will weaken the tendon and make it more likely to tear.

Risk Factors

Because most rotator cuff tears are largely caused by the normal wear and tear that goes along with aging, people over 40 are at greater risk.

People who do repetitive lifting or overhead activities are also at risk for rotator cuff tears. Athletes are especially vulnerable to overuse tears, particularly tennis players and baseball pitchers. Painters, carpenters, and others who do overhead work also have a greater chance for tears.

Although overuse tears caused by sports activity or overhead work also occur in younger people, most tears in young adults are caused by a traumatic injury, like a fall.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of a rotator cuff tear include:

- Pain at rest and at night, particularly if lying on the affected shoulder

- Pain when lifting and lowering your arm or with specific movements

- Weakness when lifting or rotating your arm

- Crepitus or crackling sensation when moving your shoulder in certain positions

Tears that happen suddenly, such as from a fall, usually cause intense pain. There may be a snapping sensation and immediate weakness in your upper arm.

Tears that develop slowly due to overuse also cause pain and arm weakness. You may have pain in the shoulder when you lift your arm, or pain that moves down your arm. At first, the pain may be mild and only present when lifting your arm over your head, such as reaching into a cupboard. Over-the-counter medication, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, may relieve the pain at first.

Over time, the pain may become more noticeable at rest, and no longer goes away with medications. You may have pain when you lie on the painful side at night. The pain and weakness in the shoulder may make routine activities such as combing your hair or reaching behind your back more difficult.

It should be noted that some rotator cuff tears are not painful. These tears, however, may still result in arm weakness and other symptoms.

Doctor Examination

Medical History and Physical Examination

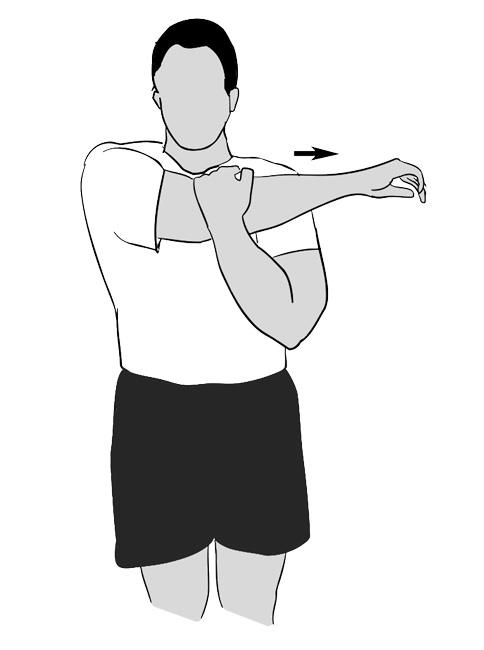

After discussing your symptoms and medical history, your doctor will examine your shoulder. He or she will check to see whether it is tender in any area or whether there is a deformity. To measure the range of motion of your shoulder, your doctor will have you move your arm in several different directions. He or she will also test your arm strength.

Imaging Tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

- X-rays. The first imaging tests performed are usually x-rays. Because x-rays do not show the soft tissues of your shoulder like the rotator cuff, plain x-rays of a shoulder with rotator cuff pain are usually normal or may show a small bone spur.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound. These studies can better show soft tissues like the rotator cuff tendons. They can show the rotator cuff tear, as well as where the tear is located within the tendon and the size of the tear. An MRI can also give your doctor a better idea of how “old” or “new” a tear is because it can show the quality of the rotator cuff muscles.

Treatment

If you have a rotator cuff tear and you keep using it despite increasing pain, you may cause further damage. A rotator cuff tear can get larger over time.

Chronic shoulder and arm pain are good reasons to see your doctor. Early treatment can prevent your symptoms from getting worse. It will also get you back to your normal routine that much quicker.

The goal of any treatment is to reduce pain and restore function. There are several treatment options for a rotator cuff tear, and the best option is different for every person. In planning your treatment, your doctor will consider your age, activity level, general health, and the type of tear you have.

There is no evidence of better results from surgery performed near the time of injury versus later on. For this reason, many doctors first recommend management of rotator cuff tears with physical therapy and other nonsurgical treatments.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In about 80% of patients, nonsurgical treatment relieves pain and improves function in the shoulder.

Nonsurgical treatment options may include:

- Rest. Your doctor may suggest rest and limiting overhead activities. He or she may also prescribe a sling to help protect your shoulder and keep it still.

- Activity modification. Avoid activities that cause shoulder pain.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling.

- Strengthening exercises and physical therapy. Specific exercises will restore movement and strengthen your shoulder. Your exercise program will include stretches to improve flexibility and range of motion. Strengthening the muscles that support your shoulder can relieve pain and prevent further injury.

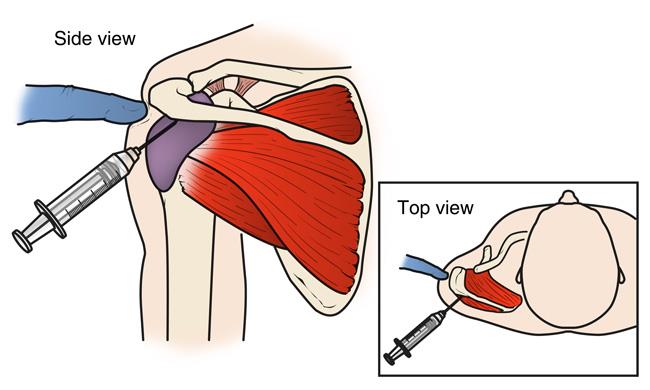

- Steroid injection. If rest, medications, and physical therapy do not relieve your pain, an injection of a local anesthetic and a cortisone preparation may be helpful. Cortisone is a very effective anti-inflammatory medicine; however, it is not effective for all patients.

The chief advantage of nonsurgical treatment is that it avoids the major risks of surgery, such as:

- Infection

- Permanent stiffness

- Anesthesia complications

- Sometimes lengthy recovery time

The disadvantages of nonsurgical treatment are:

- Size of tear may increase over time

- Activities may need to be limited

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your pain does not improve with nonsurgical methods. Continued pain is the main indication for surgery. If you are very active and use your arms for overhead work or sports, your doctor may also suggest surgery.

Other signs that surgery may be a good option for you include:

- Your symptoms have lasted 6 to 12 months

- You have a large tear (more than 3 cm) and the quality of the surrounding tissue is good

- You have significant weakness and loss of function in your shoulder

- Your tear was caused by a recent, acute injury

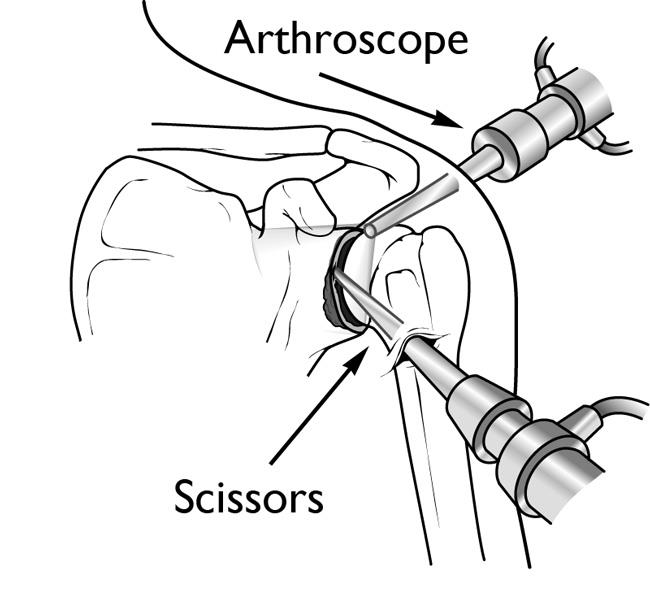

Surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff most often involves re-attaching the tendon to the head of humerus (upper arm bone). There are a few options for repairing rotator cuff tears. Your orthopaedic surgeon will discuss with you the best procedure to meet your individual health needs.