Patient Education English

- Home

- Patient Education English

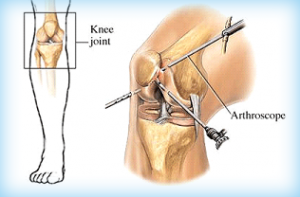

Arthroscopy is a minimally invasive surgical procedure that allows an orthopedic surgeon to see and operate inside a joint using a device called an arthroscope. The arthroscope is inserted through very small incisions in the skin.

An arthroscope is a pen-shaped instrument to which a tiny video camera and light source is attached. Lenses inside the arthroscope magnify images from inside a joint up to 30 times their normal size. These images are transmitted to a TV monitor, giving the orthopedic surgeon an exceptionally clear view of the inside of a joint. From this view, the surgeon can then operate inside the joint using small instruments inserted through separate tiny incisions. Joint surgery has improved greatly since the arthroscope was introduced. Surgery is less traumatic, healing is faster, scarring is reduced, and recovery is quicker. Only a number of tiny scars remain to show that surgery was ever done.

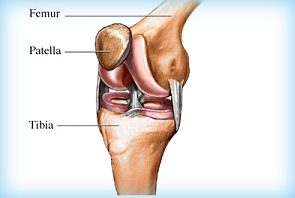

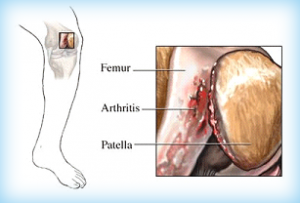

The knee is a hinged joint made up of three bones held firmly together by ligaments that stabilize the joint. The bones that meet at the knee are the upper leg bone (the femur), the lower leg bone (the tibia) and the knee cap (the patella). The bones inside the joint are lined by a smooth protective layer called articular cartilage, which allows the bones to glide smoothly upon each other. In arthritis, this smooth lining becomes damaged.

Ligaments

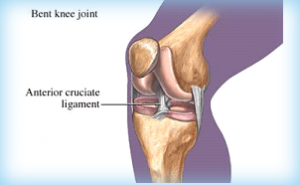

Ligaments are dense structures of connective tissue that fasten bone to bone and stabilize the knee. Inside the knee joint are two major ligaments.

- The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)

- The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)

These cross in the center of the knee (that’s why they’re called cruciate ligaments) and control the backward and forward motion of the knee. The ACL is frequently injured in severe twisting injuries of the knee. Two other major ligaments are actually located outside the knee joint, on the outer and inner side of the leg. They act to stabilize the knee’s sideways motion. The ligament on the inner side of the knee is called the medial collateral ligament or MCL (medial means inner side). The ligament on the outer side of the knee is the lateral collateral ligament or LCL (lateral means outer side). The patellar ligament (the ligament of the knee cap) connects the lower part of the patella to the upper part of the tibia, specifically to the bony prominence one can feel on the lower leg bone (the tibia). The central one-third of this ligament is the most commonly used graft source in reconstructing a torn ACL.

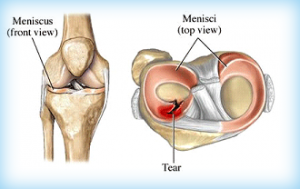

Meniscus

The meniscus is a half-moon-shaped structure placed between the weight-bearing bone ends in the knee. There are two menisci in each knee, one on the inner side called the “medial meniscus” and one on the outer side called the “lateral meniscus.” The two menisci act as shock absorbers within the knee and also help spread the weight load. The meniscus is a type of cartilage, though it is different than the cartilage that lines the bones. The menisci may be torn during twisting movements of the knee.

Arthroscopy is able to deal effectively with a number of problems in the knee joint.

- Meniscal injury

- Ligament injury

- Loose bodies within the knee

- Chondromalacia of the patella

- Osteoarthritis

Meniscal injury

These are the most common knee injuries. The menisci are two pads of fibrocartilage on either side of the knee that act as cushions or shock absorbers. They also help distribute the weight load inside the knee.

- The meniscus on the inner side of the knee is called the medial meniscus (medial means ‘inner’).

- The meniscus on the outer side of the knee is called the lateral meniscus (lateral means ‘outer’).

Most tears of the meniscus result from a sudden twisting movement of the knee as often occurs in sports injuries. As the knee bends and twists, the meniscus may be pinched between the bones. This is often accompanied by a “popping” sensation. The knee is likely to swell a few hours after the injury.

The tear may occur along the inner edge of the meniscus, or, less commonly, along the outer edge. There may be just a small torn “flap” of the meniscus, or a longer so-called “bucket-handle” tear, which is a tear along the length of the meniscus. Such a tear may cause the knee joint to “lock,” meaning that the leg cannot be straightened. The menisci maybe also become damaged and torn as part of normal wear and tear within the knee joint as we age. All types of meniscal tears can be treated by arthroscopy. Because the inner part of the meniscus has no blood supply, a tear along the inner part will not heal. Treatment, therefore, involves trimming away the torn piece of the meniscus. This is done with miniature motorized instruments inserted through a tiny incision on the side of the knee. Meniscal injuries along the outer edge of the knee may be repaired rather than removed because the blood supply to this part of the meniscus is better, giving an improved chance of healing.

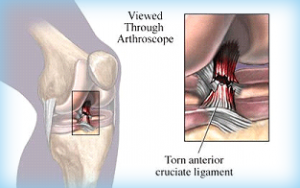

Ligament Injury

Ligaments are strong bands of tissue that fasten the bone ends together and stabilize the joint. There are two ligaments inside the knee that can be reconstructed with the assistance of the arthroscope:

- The “anterior cruciate ligament” (ACL).

- The “posterior cruciate ligament” (PCL), which is less frequently injured.

The cruciate ligaments restrict both the forward and backward motion of the knee and its rotation. They may be torn by sudden twisting motions of the knee beyond its normal range.

Not all cruciate ligament injuries need to be reconstructed; it depends on your age, level of activity, type of activity, and what you expect from your knee. A frank discussion with your doctor will help both of you determine whether surgery would be beneficial.

- If you enjoy active sports, it would be appropriate to have surgery.

- If you have a sedentary-type job and are not active in your leisure time, you may not require surgery.

Unfortunately, a simple repair by suturing the torn ligament together again is not effective. A successful repair involves completely replacing the torn ligament. There are a number of ways to accomplish this, depending on the preference of the surgeon.

- Ligament reconstruction is most commonly performed utilizing the patella tendon graft. The orthopedic surgeon takes the central strip of the patella tendon and roots this through the knee through tunnels drilled in the tibia and femur. This creates a new ligament to replace the torn one.

- More and more surgeons are now using the hamstring tendons from the back of the knee. The surgeon folds over these tendons four times into a strong, thick band and passes it through the knee. The advantage of this technique is that the patella tendon is left intact. There does not appear to be any damage caused to the hamstring muscles. Results using this technique are extremely good. Both of these methods require an extra skin incision (about 2 inches in length) to harvest the tendons to be used.

Loose Bodies Within The Knee

A traumatic incident to the knee can cause a fragment of cartilage, or a fragment of bone attached to cartilage, to come loose and float around the joint. This condition may result from “osteochondritis dissecans” (OCD).

Depending on the size of the fragment and whether it is still attached, the orthopedic surgeon may decide to reattach it or remove it entirely. The surgeon can perform either using the arthroscope.

A number of arthritic conditions may also cause loose bodies inside the knee.

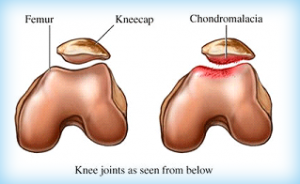

Chondromalacia Of The Patella

This is a condition in which the cartilage surface lining the kneecap softens, sometimes to the point where the articular surface cracks, giving it an irregular surface. This may lead to the discomfort felt in the front of the knee, particularly when going up and down steps.

If the problem does not respond to medication or physical therapy, some surgeons elect to smooth the rough areas of the kneecap using arthroscopic surgery.

Osteoarthritis

As we get older, our joints, including the knee, may suffer from wear and tear that can cause pain and discomfort. If medication can’t control the discomfort, your surgeon may use arthroscopy to shave and smooth the roughened surfaces of the bone and trim any damage to the meniscus.

Clearing out the debris often helps reduce the pain of arthritis for a period of time. This is a significantly less traumatic procedure than a total knee replacement, which may ultimately be required if the pain and discomfort from osteoarthritis becomes severe.

Depending on your age, certain preoperative tests will be arranged, such as blood tests, urine tests, chest x-ray, and ECG.

- For an ACL reconstruction, leg measurements may be taken to order a knee brace. Your rehabilitation program will be discussed in detail with you.

- You may meet the anesthesiologist, who may offer you a choice of anesthesia:

- If you choose a general anesthetic, you will be asleep during the procedure.

- If you choose an epidural, an injection is given into the back that numbs the lower half of the body. This wears off a couple of hours after surgery.

- If you chose a local anesthetic, you will receive injections of a local painkiller in the knee and surrounding areas.

If you have epidural or local anesthesia, you can often watch the whole operation on the television monitor as seen through the arthroscope.

Need To Know:

- You should not eat or drink anything (even water) for eight hours before surgery. This usually means not eating or drinking anything after midnight the night before surgery.

- If you would normally be taking medication during the hours before surgery, talk to your doctor.

What to tell your doctor

Be sure to tell your doctor:

- If you are allergic to iodine, penicillin, or any other drugs

- What medications you take

- About your past medical history

- If you have ever had deep vein thrombosis or other blood clotting abnormalities

Also, tell your doctor if you develop any of these symptoms prior to surgery:

- Fever or chills

- Irritation of the eyes, ears, throat, or gums

- Sniffling or sore throat

- Boils or inflamed skin abrasions and cuts

The Operation

After the chosen anesthetic has been administered, the leg is thoroughly cleaned, usually with an iodine-based solution. A tourniquet may be placed around the thigh. A tiny incision is made on the outer side of the knee about level with the lower end of the knee cap. The arthroscope is then gently introduced into the knee, so the surgeon can see the inside of the knee on the TV monitor.

Another small incision is then made on the inner side of the knee to allow the surgeon to insert specialized instruments.

- If the meniscus is torn: the torn flap or segment is carefully trimmed away, leaving a smooth edge. However, if the tear is on the outer side of the meniscus, where the blood supply is better, it is possible to repair the tear using specialized sutures.

- If the anterior cruciate ligament is completely torn: an additional two-inch incision will be required to remove either the patella tendon or hamstring tendon to create a new cruciate ligament. Tunnels are drilled in the tibia and femur through which the new ligament is passed. The ligament is then anchored firmly to the bone, usually with

- screws at either end or endobutton on femur and screw on the tibial side.

- If a loose body is found, treatment may vary. If it is truly loose and floating around the joint, it can be easily removed. If it is still partially attached, it can be gently pushed back into place and held with a specialized scre

- If the problem is arthritis or chondromalacia, the roughened surface may be smoothed with power instruments. The surgeon will also remove any bits of bone or cartilage floating in the joint.

- You will usually have recovered enough to be driven home a few hours after the surgery. You may or may not be allowed to put weight on your knee immediately after surgery, depending on what was done to your knee. A physical therapist will help you get mobile with crutches before going home.

- Expect some swelling and discomfort in the knee for a few days. You will be given a prescription for pain medication and an anti-inflammatory drug to deal with the swelling.

Need To Know:

Tips to help your recovery

- Elevate your leg on a couple of pillows to reduce swelling.

- Ice the knee periodically for about 10 – 15 minutes at a time during the first week. Do not apply the ice directly to the knee, but wrap the ice in a waterproof pack, which you can then wrap in a towel and place on your knee. Take the medications prescribed by your doctor.

- Move your ankles up and down. This simple exercise, called “ankle pumps,” is important for preventing possible blood clots in the leg.

- Use crutches if you have been told to keep weight off the knee.

- Do the exercises you have been told to do in order to quickly regain the strength in your leg.

- Gradually increase your walking as instructed by your orthopedic surgeon or physical therapist.

- If you have been fitted with a brace, be sure to wear it.

Caring For The Incision

Sutures may or may not have been used to close the wounds. Your doctor will instruct you when you may remove the bandage, usually within a day or two (depending on the procedure), leaving smaller dressings over the actual incisions. Your doctor will let you know how long to wait before you can get your knee wet, but in general, do not get your knee wet until the sutures are removed. You will need to cover the leg with a large plastic bag when bathing, to keep the incision dry for the first week to 10 days.

Need To Know:

When to contact your doctor

There are very few complications that occur after arthroscopy, but you should be aware of the possibility of postoperative problems. Contact your doctor if:

- There is increasing pain and swelling in the knee

- The knee becomes increasingly red

- Fluid or pus oozes from a wound

- You have a fever

- You have pain and tenderness in the calf muscle (this may suggest a clot in the veins)

- You have chest pain (this may suggest a blood clot in the lung).

Importance of Exercise Before You Start Initial Exercise Program Intermediate Exercise Program Advanced Exercise Program

Importance of Exercise

Regular exercise to restore your knee mobility and strength is necessary. For the most part, this can be carried out at home.

Your orthopedic surgeon may recommend that you exercise approximately 20 to 30 minutes two or three times a day. You also may be advised to engage in a walking program.

Before you leave your home, create a medical history form that includes the following information:

Before You Start

Your orthopaedic surgeon may suggest some of the following exercises. The following guide can help you better understand your exercise or activity program that may be supervised by a therapist at the direction of your orthopaedic surgeon.

As you increase the intensity of your exercise program, you may experience temporary setbacks. If your knee swells or hurts after a particular exercise activity, you should lessen or stop the activity until you feel better.

You should Rest, Ice, Compress (with an elastic bandage), and Elevate your knee (R.I.C.E.). Contact your orthopaedic surgeon if the symptoms persist.

Initial Exercise Program

Hamstring Contraction – Repeat 10 times.

No movement should occur in this exercise. Lie or sit with your knees bent to about 10 degrees. Pull your heel into the floor, tightening the muscles on the back of your thigh. Hold 5 seconds, then relax.

No movement should occur in this exercise. Lie or sit with your knees bent to about 10 degrees. Pull your heel into the floor, tightening the muscles on the back of your thigh. Hold 5 seconds, then relax.

Quadriceps Contraction – Repeat 10 times.

Lie on your stomach with a towel roll under the ankle of your operated knee. Push ankle down into the towel roll. Your leg should straighten as much as possible. Hold for 5 seconds. Relax.

Lie on your stomach with a towel roll under the ankle of your operated knee. Push ankle down into the towel roll. Your leg should straighten as much as possible. Hold for 5 seconds. Relax.

Straight Leg Raises – Repeat 10 times.

Lie on your back, with the uninvolved knee bent, straighten your involved knee. Slowly lift about 6 inches and hold for 5 seconds. Continue lifting in 6-inch increments, hold each time. Reverse the procedure, and return to the starting position.

Advanced: Before starting, add weights to your ankle, starting with 1 pound of weight and building up to a maximum of 5 pounds of weight over 4 weeks.

Buttock Tucks – Repeat 10 times.

While lying down on your back, tighten your buttock muscles. Hold tightly for 5 seconds.

While lying down on your back, tighten your buttock muscles. Hold tightly for 5 seconds.

Straight Leg Raises, Standing – Repeat 10 times.

Support yourself, if necessary, and slowly lift your leg forward keeping your knee straight. Return to the starting position. Advanced: Before starting, add weights to your ankle, starting with 1 pound of weight and building up to a maximum of 5 pounds of weight over 4 weeks.

Support yourself, if necessary, and slowly lift your leg forward keeping your knee straight. Return to the starting position. Advanced: Before starting, add weights to your ankle, starting with 1 pound of weight and building up to a maximum of 5 pounds of weight over 4 weeks.

Intermediate Exercise Program

Terminal Knee Extension, Supine – Repeat 10 times.

Lie on your back with a towel roll under your knee. Straighten your knee (still supported by the roll) and hold 5 seconds. Slowly return to the starting position.

Advanced: Before starting, add weights to your ankle, starting with 1 pound of weight and building up to a maximum of 5 pounds of weight over 4 weeks.

Straight Leg Raises – Repeat 10 times.

Lie on your back, with your uninvolved knee bent. Straighten your other knee with a quadriceps muscle contraction. Now, slowly raise your leg until your foot is about 12 inches from the floor. Slowly lower it to the floor and relax.

Advanced: Before starting, add weights to your ankle, starting with 1 pound of weight and building up to a maximum of 5 pounds of weight over 4 weeks.

Partial Squat, with Chair – Repeat 10 times.

Hold onto a sturdy chair or counter with your feet 6-12 inches from the chair or counter. Do not bend all the way down. DO NOT go any lower than 90 degrees. Keep back straight. Hold for 5-10 seconds. Slowly come back up. Relax.

Hold onto a sturdy chair or counter with your feet 6-12 inches from the chair or counter. Do not bend all the way down. DO NOT go any lower than 90 degrees. Keep back straight. Hold for 5-10 seconds. Slowly come back up. Relax.

Quadriceps Stretch, Standing – Repeat 10 times.

Standing with the involved knee bent, gently pull heel toward buttocks, feeling a stretch in the front of the leg. Hold for 5 seconds.

Standing with the involved knee bent, gently pull heel toward buttocks, feeling a stretch in the front of the leg. Hold for 5 seconds.

Advanced Exercise Program

Knee Bend, Partial, Single-Leg – Repeat 10 times.

Stand supporting yourself with the back of a chair. Bend your uninvolved leg with your toe touching for balance as necessary. Slowly lower yourself, keeping your foot flat. Do not overdo this exercise. Straighten up to the starting position. Relax.

Stand supporting yourself with the back of a chair. Bend your uninvolved leg with your toe touching for balance as necessary. Slowly lower yourself, keeping your foot flat. Do not overdo this exercise. Straighten up to the starting position. Relax.

Step-ups, Forward – Repeat 10 times.

Step forward up onto a 6-inch high stool, leading with your involved leg. Step down, returning to the starting position. Increase the height of the platform as strength increases.

Step forward up onto a 6-inch high stool, leading with your involved leg. Step down, returning to the starting position. Increase the height of the platform as strength increases.

Step-ups, Lateral – Repeat 10 times.

Step up onto a 6-inch high stool, leading with your involved leg. Step down, returning to the starting position. Increase the height of the platform as strength increases.

Step up onto a 6-inch high stool, leading with your involved leg. Step down, returning to the starting position. Increase the height of the platform as strength increases.

Terminal Knee Extension, Sitting – Repeat 10 times.

While sitting in a chair, support your involved heel on a stool. Now straighten your knee, hold 5 seconds, and slowly return to the starting position.

While sitting in a chair, support your involved heel on a stool. Now straighten your knee, hold 5 seconds, and slowly return to the starting position.

Hamstring Stretch, Supine – Repeat 10 times.

Lie on your back. Bend your hip, grasping your thigh just above the knee. Slowly straighten your knee until you feel the tightness behind your knee. Hold for 5 seconds. Relax. Repeat with the other leg.

If you do not feel this stretch, bend your hip a little more, and repeat.

No bouncing! Maintain a steady, prolonged stretch for the maximum benefit.

Hamstring Stretch, Supine at Wall – Repeat 10 times.

Lie next to a doorway with one leg extended. Place your heel against the wall. The closer you are to the wall, the more intense the stretch. With your knee bent, move your hips toward the wall. Now begin to straighten your knee. When you feel the tightness behind your knee, hold for 5 seconds. Relax.

Repeat with the other leg.

Exercise Bike – Repeat 10 times.

If you have access to an exercise bike, set the seat high so your foot can barely reach the pedal and complete a full revolution. Set the resistance to “light” and progress to “heavy.”

Increase the duration by one minute a day until you are pedaling 20 minutes a day. Walking

Excellent physical exercise activity in the middle stages of your recovery from surgery (after 2 weeks).

Running should be avoided until 6 to 8 weeks because of the impact and shock forces transmitted to your knee. Both walking and running activities should be gradually phased into your exercise program.

HOW LONG UNTIL FULL RECOVERY?

Recovery time will depend on the procedure performed.

- If a partially torn meniscus was removed – You should be back to full activities within four to six weeks.

- If a partially torn meniscus was repaired – You should expect four to six months until full recovery.

- If you had an ACL reconstruction – You should commit to an aggressive rehabilitation program and expect full recovery in six to nine months (but you can be back at a desk job within a week or two).

- If you had loose bodies removed – Recovery may take two to four weeks.

- If you had a loose body repaired – Recovery is usually six to eight weeks.

- If you had chondromalacia or arthritis – You should expect a couple of weeks to recover.

When To Return To Work?

Return to work will depend on your job and the procedure that was done. Generally:

- If you have a desk job, you could return to work within one week. Try to keep your foot elevated initially to prevent swelling. Get up for a short walk at least every hour for the first few weeks.

- If you stand most of the day but do not lift heavy objects, you’ll probably be ready to return to work within four to six weeks.

- If your job requires climbing or lifting heavier objects, recovery time will depend on the procedure. You may need to wait two to four months before returning to work and initially avoid lifting objects that weigh more than 10 lbs

1. How can a meniscus be torn?

The medial and lateral menisci are fixed between the two weight-bearing surfaces within the knee, and as such can become “pinched” by the other structures of the knee between the joint when an injury occurs. Typically, the injury involves twisting on a bent knee. When this happens the menisci can become torn (“torn cartilage”). Any form of physical movement can potentially cause a meniscal tear, although they tend to be associated with sporting activities. A classic example is of a footballer tackling another player, but meniscal tears can occur following everyday pursuits, such as gardening or even just taking a long walk.

2. Can a meniscal tear heal by itself?

Most of the meniscus does not have its own blood supply, and so cannot always get the nutrients needed for self-repair. Whether or not the meniscus can heal therefore depends on where it becomes torn. Tears on the outer rim of the meniscus, which attaches to the knee capsule, do have the potential to heal because they are close to a blood supply. However, the more common site for meniscal tears is on the peripheral rim, or the inner aspect of the meniscus and these have no capacity for self-repair.

3. What are the symptoms of a meniscal tear?

The classic symptom of a torn meniscus is pain, often felt as a sharp, almost “knife-like” stabbing sensation on the inside (medial tear) or outside (lateral tear) of the knee. This pain is often felt in waves, with bouts of severe discomfort, followed by no pain, felt over the course of several days/weeks. However, the pain may also be felt as an aching sensation or even just as the stiffness of the knee. The knee may also become swollen or “locked” in place, making it impossible to straighten it, or even collapse, or give the impression that it will collapse, from beneath you.

4. How does the doctor know I have a meniscal tear?

A meniscal tear can be diagnosed based on your description of how your injury occurred, and by taking a specialized photograph of your knee known as a magnetic resonance imaging or MRI scan. An MRI scan uses very strong magnetic fields to look at the inside of the knee and allows all the soft tissues, ligaments, and cartilage to be seen clearly. X-rays are not very useful in making a diagnosis, as these show only the bony structures of the knee, but may be used in the emergency setting to check that there are no broken bones.

5. How do you treat a meniscal tear?

Meniscal tears are treated using arthroscopic or keyhole surgery, but not everyone will need surgery. As with all injuries there are options and the most important thing to be considered is the level of discomfort and whether it interferes with your ability to function normally. All surgical procedures carry some element of risk, and your doctor must ensure that the benefits of any treatment you receive outweigh any potential risks.

6. How long do I need to stay in the hospital after arthroscopic surgery?

Arthroscopic surgery is usually performed as a “day case,” meaning that you can go home the same day as the operation. Some people may need to stay in the hospital for a couple of days to recover from the operation, but your surgeon will advise you on this.

7. How long will it take to recover from arthroscopic surgery?

This depends on the procedure being performed, but in the case of arthroscopic meniscectomy, which is the commonest procedure, you will generally be able to walk unaided the same day. Your doctor will recommend that you take at least four to five days off work. The time needed will depend on the type of work that you do, and people with physically demanding jobs may be advised to take a minimum of two weeks off work.

8. When will I start to feel better after arthroscopic surgery?

Although it depends on your injury and the type of surgery being performed, you should start to feel better within a couple of weeks and may be able to participate in certain sporting activities (eg, going to the gymnasium) for approximately a month or so after the operation. It could however take several months before you are able to train fully or as you would normally. Your doctor will again advise you on the details of this.

9. What and where is the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)?

The ACL is a ligament in the middle of the knee that connects the tibia (shinbone) to the fibia (thighbone).

10. What are the symptoms of an ACL injury?

A key feature of a serious ACL injury is a feeling of instability (i.e. that the knee may collapse from underneath you).

11. Do I need to have surgery on my ACL?

Not always. Some people are able to function normally without surgery, so long as they have physiotherapy, but others need reconstructive surgery no matter how much physiotherapy they have. Whether or not you have your ACL reconstructed also depends on how active you are, and how your injury impacts on your daily and sporting activities.

12. Is physiotherapy necessary before ACL reconstruction?

Early surgical intervention to repair a torn ACL is not recommended in the vast majority of cases, and physiotherapy for at least four to six weeks is almost always recommended first in the amateur sportsperson. This approach has the advantage of allowing any other associated injuries to settle, and any inflammation to subside. Taking time to have physiotherapy also gives the patient and physiotherapist the opportunity to assess whether they feel there is a genuine need for reconstruction.

13. Should I wear a knee brace to support my knee rather than undergo major surgery for ACL reconstruction?

Many older people find that wearing a well fitted, ACL-specific knee brace gives them the confidence and stability to return to the sport they enjoyed previously without the need for surgery.